The web site of Dr. Claire Gapper

Chapter IV

From timber to plaster: courtly ceilings in the sixteenth century

Introduction

Most accounts of English decorative plasterwork take as their starting point the panels applied to the exterior of Nonsuch Palace in the early 1540s. This is to ignore the evidence of experimentation with plaster as a decorative medium in England before this date and leads to over-simplification in the account of subsequent developments. The history of decorative plasterwork in the mid-sixteenth century is one of interwoven strands, which the paucity of evidence makes it difficult to unravel, but the following account will attempt to clarify the issues and suggest some alternative interpretations of the surviving evidence.

No attempt will be made in this chapter to survey the history of decorative plasterwork in the sixteenth century across the whole of the British Isles, either socially or geographically. The regional studies of plasterwork which have so far been undertaken are too few in number to make such an enterprise practicable, and detailed studies of some of the most important centres, such as Bristol, remain to be attempted. It may well be that the great quantity of excellent plasterwork surviving in West Country houses of gentry and yeomen, dating from the middle of the sixteenth century onwards, represents experimentation with the new decorative medium that was to prove influential in the region; but further research is needed in this and many other localities to test this hypothesis further.

This study will, therefore, concentrate on the evidence (material and documentary) which points to the influential role played by the court in the dissemination of new fashions in ceiling decoration in the sixteenth century. In the first part of this chapter the innovative ceilings which were designed for Cardinal Wolsey and Henry VIII in timber and plaster in the first half of the century will be examined, and the contribution of Nicholas Bellin of Modena to the development of English plasterwork assessed. This will be followed by a consideration of the role of royal palaces and aristocratic and senior courtier houses in the expression of these new fashions, in the medium of plaster, in the second half of the century.

Although the number of examples of decorative plasterwork which fall within this last category is rather small, the houses in which they occur are scattered widely across the British Isles. The majority of them were located in London and southern England (and generalisations will refer to English plasterwork) but the Midlands, the north of England and Ireland are also represented. Reference will also be made to plasterwork in Wales but there were no parallel developments in Scotland until later in the sixteenth century.

Decorative plasterwork was used in the second half of the sixteenth century to ornament three specific areas of the English interior, singly or in conjunction: the ceiling, the frieze and the chimneypiece. In all three areas plasterwork drew inspiration from developments which had already taken place in interior decoration using other materials, namely timber and stone. Throughout the period under discussion, friezes continued to be carved in wood, and chimneypieces in wood or stone, alongside their plaster counterparts. Only on the ceiling did plaster come to dominate the decorative scene in England in a manner which was unknown in the rest of Europe. However, as the plasterers at first followed very closely in the footsteps of the joiners who were responsible for much of the innovatory ceiling decoration of the first decades of the sixteenth century, some account must first be taken of developments in ceiling design in those years, a period of rapid change in interior decoration as a whole.

Early developments in ‘ceiling’

Timber ceilings

From the fourteenth century onwards, rooms were increasingly provided with mural fireplaces which meant that they no longer had to be left open to the roof to allow smoke to escape from an open hearth. Now they could be boarded or plastered to 'ceil' them, reducing draughts and dirt. The creation of flat timber ceilings was not unknown in medieval palaces, but their costliness restricted their use to the houses of the wealthy.[1] It should also be pointed out here that ‘ceiling’ was an alternative spelling for ‘sealing’ and could refer to the covering of walls as well as ceilings, whether with plaster or timber panelling.

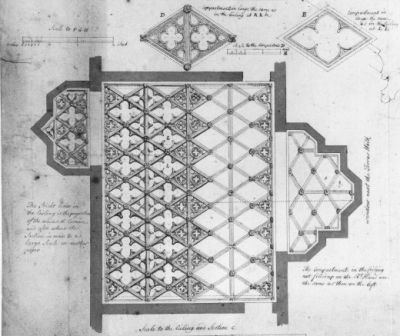

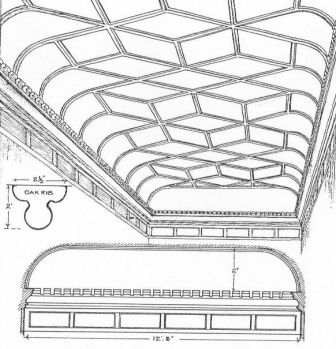

Flat timber ceilings were created in one of two ways: sometimes with a slight pitch, sometimes completely flat. They could be entirely boarded with planks, creating a flat field to which wooden battens were then applied in a variety of rectilinear patterns, usually based on squares or lozenges. These designs were known as 'fretwork', regardless of their style or the materials used in their execution. A particularly rich effect was obtained by the insertion of carved wooden tracery or cusping in the panels so created, as on the ceiling of the 'Beauty Room' in Henry VII's tower at Windsor Castle (1500-02) (Fig. 7).

Many of the patterns produced with ribs or battens on the flat surfaces of these timber ceilings are to be found in medieval churches, executed in stone or timber on curved vaults or flat roofs. The continuity of this tradition of roof decoration was to prove an important strand not only in the design of decorative plaster ceilings but also in their embellishment. Links with the medieval past are particularly apparent in the practice of placing bosses and/or pendants at the intersections of the beams or ribs, familiar from several centuries of ecclesiastical masonry and timber vaulting. On domestic timber ceilings this practice may have served a functional purpose, since it concealed any failures in the mitreing; but the bosses also helped to break up the expanse of relatively flat surface in the larger ceilings. Both bosses and pendants might also be ornately carved, increasing the decorative effect of the ceiling. The four leaves which typically radiated from the bosses into the corners of the rectilinear panels were more likely to be made of lead than wood, so that they could be bent up onto the ceiling more easily.[2]

Fig. 7. A measured drawing of the ceiling of the ‘Beauty Room’ at Windsor Castle (1500-02).

Documentary records provide no certain evidence as to the specific appearance of patterned ceilings since all rib designs were termed ‘frets’. For example, when Richard Ridge, a joiner, set up new battens in the roof of the king’s privy chamber at Greenwich in 1536-37 ‘after the anttycke faccon’, this may refer to the layout of the ribs but is just as likely to refer to the enrichment of the battens themselves, for which gilded lead ‘antick’ was supplied by John Hethe.[3]

However, documentation is invaluable for another entirely traditional element that emerged in the decoration of the panels between the timber battens of the ceilings of Tudor royal palaces. Heraldry played a key role in this area, as evidenced by the plethora of heraldic badges, mottoes, cyphers and coats-of-arms that were listed.

An alternative method of 'ceiling' was to leave the main structural timbers exposed, using moulded timber ribs to break up the rectilinear fields, laying them in parallel with the larger beams to create smaller squares or rectangles. Decorative carving of the woodwork added greatly to the ornamental effect of this form of ceiling, which continued to be constructed throughout the sixteenth century. They could, however, easily appear overwhelming if not scaled to suit the size of the room, as in the Withdrawing Room at Little Moreton Hall, Cheshire (c.1559), where the great timbers of the ceiling bear down oppressively on the spectator (Fig. 51).[4] Such a quantity of expensive oak must have resulted in a rather gloomy interior and this was no doubt the prime reason for the increasing use of plaster on ceilings.

Timber and plaster ceilings

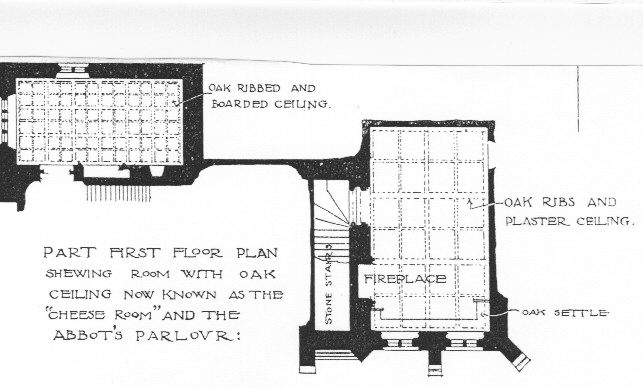

At Muchelney Abbey, Somerset (c.1470) the ‘Cheese Room’ was ceiling entirely in oak but in the Abbot's Parlour a much brighter effect was achieved. The structural timbers remained exposed but the rectangular fields they created were filled with plaster, on which were laid moulded wooden ribs, sub-dividing the fields into smaller rectangles (Fig. 8). This ceiling must have demonstrated very clearly the advantages of plaster over timber in terms of lightness and, probably, expense. This format, of a ceiling divided into quarters by the main cross beams, with the areas between the beams plastered, survived well into the seventeenth century and will be encountered again during the discussion of decorative plasterwork later in this study.

Fig. 8. Plan showing layout of ceilings at Muchelney Abbey, Somerset. (From T Garner & A Stratton, The Domestic Architecture of England during the Tudor Period, 1911).

Early decorative plaster ribs and bosses

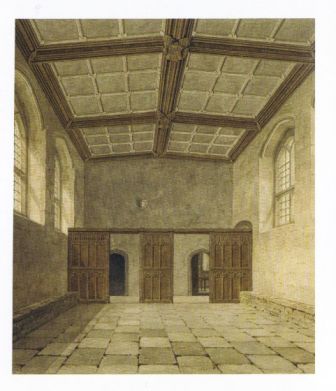

A more significant step, from the point-of-view of the plasterer, was taken at Great Chalfield Manor, Wiltshire (c.1470). Although the original ceiling of the hall was demolished in the nineteenth century, it had been recorded by J C Buckler in 1823, showing that the plaster panels between the timber beams were decorated with plaster ribs. One of the square bosses that covered the intersection of the ribs survives in the house and it, too, was made using plaster (Fig. 9). Drawings were made of all the bosses, many of which were decorated with mottoes and badges of Thomas Tropenell, the builder of the house.[5] This would appear to be the earliest example of plaster used for decorative purposes on a ceiling and its appearance in a gentry house suggests that experiments with plaster were likely to occur in houses where patrons might not have had the resources to invest in a roof entirely of timber. As the hall at Great Chalfield has windows along both its long sides, considerations of lightness were probably not the prime motivation in the choice of plaster rather than timber.

Fig. 9. Watercolour of the hall of Great Chalfield Manor, Wiltshire, in 1823 by J C Buckler, held in the house.

Plane plaster surfaces, new timber-rib patterns and a painted ‘fret’

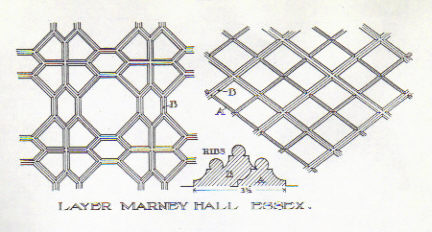

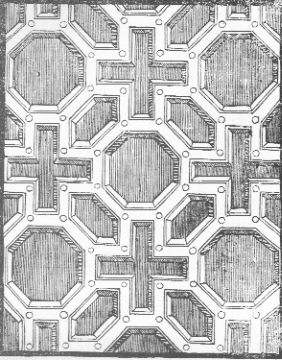

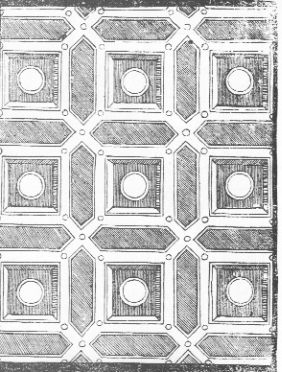

The advantages in lightness and economy must have applied equally to those ceilings where the structural timbers were completely covered and a plane surface created. Provided a smooth surface was achieved, plastering the ceiling would result in just as satisfactory a field for the application of further decoration as a timber ceiling. The ability of plasterers to achieve an even surface must have been a crucial factor in this development, and the increasing use of the designation 'plasterer', rather than 'dauber' or 'pargetter', probably reflects the growing importance of this skill. Brief mention was made in Chapter I of the use of gypsum plaster on ceilings in Henry VIII's palaces and houses to provide a smooth surface for the joiners to decorate with timber frets. This suggests that the plasterers were able to fulfil this requirement to the king's satisfaction at least by the 1530s. In fact, some of them must already have acquired the necessary expertise by the 1520s, when they were similarly employed by Cardinal Wolsey at Hampton Court and by the 1st or 2nd Lord Marney at Layer Marney, Essex, where two such ceilings have survived, which are deemed to date from the years immediately preceding the death of the 2nd Lord Marney in 1525. While one of these consists of ribs of two widths laid very simply lozenge-wise, the second combines octagons, hexagons and Greek crosses in a style more commonly associated with Italian Renaissance designs (Fig. 10), which will be discussed further below.

Fig. 10. Rib layouts on ceilings from Layer Marney Hall, Essex (early 1520s). (From T Garner & A Stratton, The Domestic Architecture of England during the Tudor Period, 1911).

When speed was essential, as was the case for Nicholas Poyntz (who had only a short time to prepare lodgings at Acton Court prior to a visit by Henry VIII in 1535), a smooth gypsum surface could be embellished with a trompe l'oeil fret pattern in oil paint as a substitute for timber ribs. As illustrated in Chapter I (Fig. 3), the ceiling of the king’s bedchamber at Acton Court was reconstructed by the archaeologist, Kirsty Rodwell, revealing a pattern of ribs painted with a central band of yellow ochre, flanked by outer borders of a darker orange-brown, to create the effect of timber ribs against a white ground.[6] The ceiling was further embellished with fully three-dimensional bosses, or 'bullions', held in place with metal pins. A geometric pattern was created on the ceiling based on a hexagonal grid of interlocking diamonds. This was complemented by a painted frieze and overmantel of early Renaissance character, similar to the friezes for which there is evidence in the other two rooms of the range. The high quality of the painting of these friezes (which is best seen in the central room) (Fig. 4) has suggested that Poyntz may have had access to artists who usually worked for the court. It is noticeable, however, that the fashionable all’antica design of the frieze, with its classicizing roundels and grotesques, is not matched by the pattern on the ceiling.

Hexagonal rib designs

This visually disconcerting pattern from Acton Court, based on regular diamonds, seems to have enjoyed some popularity in courtier houses between the 1520s and 1540s. With variations and using timber ribs it was to be found at Knole, Kent (in the Brown Gallery and Spangle Bedroom, c.1520), The Vyne, Hampshire (in the chamber over the chapel, 1525-6)

Fig. 11. The ceiling of the gallery at Bermondsey Abbey. (From T Garner & A Stratton, The Domestic Architecture of England during the Tudor Period, 1911).

and at Bermondsey Abbey, South London (in the Gallery of Sir Thomas Pope’s post-Dissolution conversion, c.1540) (Fig. 11).[7] One of the motifs that emerges is a hexagonal star made up of diamonds but it is quite difficult to focus on this outline as the eye moves over the ceiling.

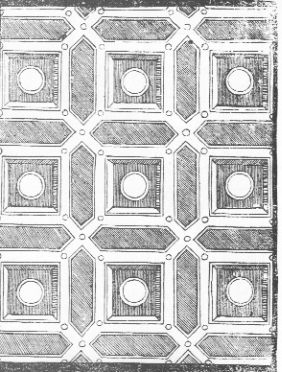

A rather different hexagonal design was devised for the ceiling of one of the rooms created in Cardinal Wolsey’s lodgings at Hampton Court between 1526 and 1528 (Fig. 12). Six-petalled flowers of a regular but unusual outline are repeated across the ceiling. Hispano-Moorish patterns come to mind as a possible source, hinting at the possibility that Katharine of Aragon may have acted as a conduit for such an influence to reach England.

However, none of these patterns was to be repeated in plaster. Whether this was because they went out of fashion or because they did not find favour with plasterers is not clear. The hexagonal grid may have proved less easy to manipulate than the rectilinear grids which formed the basis of the majority of plaster ceilings in the second half of the century.

Fig. 12. A ceiling in Cardinal Wolsey’s Lodgings, Hampton Court (1526-8). (From L Turner, Decorative Plasterwork in Great Britain, 1927).

Eight-pointed stars

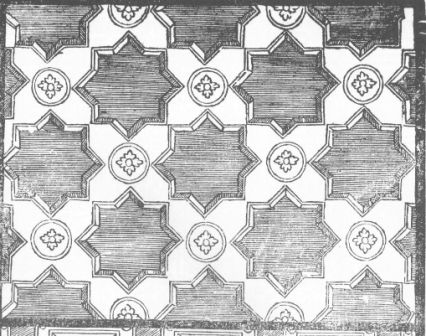

The ceilings of the Spangle Bedroom at Knole and the chamber over the chapel at The Vyne are not confined to hexagonal outlines but also include an eight-pointed star which was to prove one of the most enduringly popular design motifs throughout the sixteenth century. It is made up of eight kite-shaped panels and plasterers found that they could create a wide diversity of patterns based on it, by the addition of ribs or by overlapping the outlines. An early variant can be seen in another of Cardinal Wolsey’s ceilings at Hampton Court (Fig. 13) and it will be encountered again and again on plaster ceilings.

Decorated timber ribs for Cardinal Wolsey and Henry VIII

In his perpetual striving for novelty and opulence the overweening cardinal was one of the most influential builders and innovative interior decorators in the second and third decades of the sixteenth century. Two ceilings in what were his lodgings at Hampton Court are the only survivors from the numerous sumptuous interiors which drew paeans of praise from overseas visitors (Fig.12-13).[8] It is for the decoration of their ribs that they are particularly significant. Although the ribs of the ceilings were still made of wood, they represented a new departure in the experimental technique of their construction. Instead of carving the timber ribs to increase their decorative value, strips of‘grotesquework’ cast in lead were slotted along the centre.

Fig. 13. A ceiling in Cardinal Wolsey’s lodgings, Hampton Court (1526-8) (From L Turner, Decorative Plasterwork in Great Britain, 1927).

This type of Early Renaissance ornament was referred to as 'antick' in the royal accounts of the following decade, when the technique was applied to ceilings created for Henry VIII. When his Holyday Closet was decorated in 1536, strips of 'antick' from the same moulds used on Wolsey’s ceilings were attached along both sides of the ribs that were laid out in another variant of the eight-pointed star. Grotesquework was one of the most influential elements of antique Roman decoration recovered during excavations in Rome in the late fifteenth century. There is, however, no evidence that any of the Italian artists working for Henry were involved in the actual production of the 'antick' elements for the interiors of his palaces; the names of the craftsmen involved which appear in the accounts are either English, Flemish or German.[9] By the time that plasterers were creating enriched ribs, towards the end of the century, ‘antick’ was no longer in fashion; but it seems highly likely that it was these ceilings at Hampton Court that inspired plasterers to experiment with the decoration of their ribs.

Ceilings for Henry VIII

Bosses and pendants

Ceilings embodying the eight-pointed star motif point to the continuity within the native tradition of the influence of masonry ribbed vaulting. This was markedly reinforced by the application to timber-rib ceilings of bosses and pendants. The decoration of the intersections of ribs in this way was to continue on wholly plaster ceilings throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It is in the Great Watching Chamber at Hampton Court that the earliest known surviving examples of pendants decorating a wood-and-plaster ceiling are to be found. (Fig. 14). In October 1535 a joiner turned twenty-five timber pendants for the fret of the roof, which were then cut and carved by Richard Ridge. Some weeks later Ridge was responsible for making, finishing and setting up the fret in the roof, the pendants requiring iron 'vices' (screws) for fixing them in place.[10] The pendants were not simply attached to the flat ceiling, but where the ribs met at the centre of the stars they were pulled downwards and the pendants then screwed on. Here is an echo of the kind of Gothic vaulting which was familiar in England from ecclesiastical examples and it is noteworthy that this interruption of the flat plane of the ceiling and the attachment of pendants were both features which played a significant role in later plaster ceilings. The ceiling of the Inlaid Chamber at Sizergh Castle, Westmorland (c.1580) is but one of several examples which reproduce the Great Watching Chamber entirely in plaster (Fig. 44).

Documentary sources indicate that pendants very often continued to be made of wood, rather than plaster, for lightness. Extremely large pendants, such as the one over the staircase at Blickling Hall, Norfolk, were usually carved by a joiner, in this case, by Robert Lyming in 1628 (Fig. 16).[11] Once whitewash has been applied the difference in material is not normally visible to the naked eye, but at Hardwick Court, Oxfordshire, one of the pendants has slipped out of place and left exposed the cracked wood of its unpainted spindle (Fig. 16).

Fig. 14. The ceiling of the Great Watching Chamber, Hampton Court (1535). (From Joseph Nash, Mansions of England in the Olden Time, 1839).

Fig. 14. The ceiling of the Great Watching Chamber, Hampton Court (1535). (From Joseph Nash, Mansions of England in the Olden Time, 1839).

Fig. 15. The pendant in the ceiling originally over the Great Stairs at Blickling Hall, Norfolk (c.1620).

Fig. 16. A boss showing its timber spindle on the ceiling of the Great Chamber, Hardwick Court, Oxon (c.1610).

Serlian designs for Henry VIII

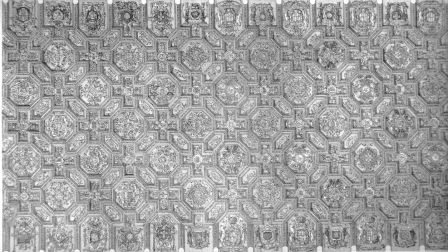

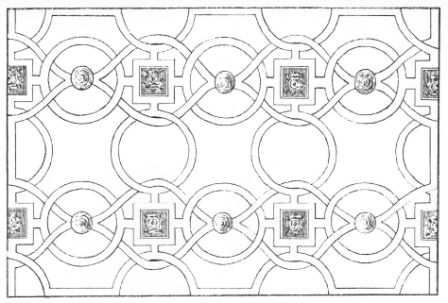

In his pursuit of fashion and novelty Henry VIII created two ceilings of great elaboration and richness dating from c.1540. One of these was the ceiling of the Chapel Royal at St James's Palace, which bears the date 1540, and the presence of numerous heraldic motifs associated with Anne of Cleves, who married Henry VIII in that year, confirms that this date was not a later addition (Fig. 18). The wooden panels painted with these motifs are set within a timber framework of narrow ribs, enriched with the same kind of lead 'antick' as at Hampton Court. The pattern created by the ribs is

derived from an antique Roman, but Christian, source in the ambulatory of the church of Santa Costanza.[12] The pattern had been used by Peruzzi to decorate a ceiling of the Cancelleria in 1520 and was subsequently included by Sebastiano Serlio (who had been apprenticed to Peruzzi) among the designs for ceilings in his Regole Generale di Architettura, published in Venice in 1537, where no reference is made to the ecclesiastical source of the pattern (Figs. 18 &19).[13]

Fig. 17. Ceiling of the Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace (c.1540). (C J Richardson, Architectural Remains of the Reigns of Elizabeth and James I (1838).

Fig. 18. Serlio, Book IV, f. 68v, top left (Dover facsimile of The Five Books of Architecture, 1611).

Fig. 19. Serlio, Book IV, f. 69r, bottom right (Dover facsimile of The Five Books of Architecture, 1611).

This design was, however, known in England prior to the appearance of Serlio's published volumes. Its earliest manifestation in this country would appear to be in the ceiling at Layer Marney of the early 1520s (Fig. 10). In truncated form it figured in the woodcarving decorating the screen and stalls of another chapel - that of King's College, Cambridge. This was also a royal commission and it, too, can be dated by the carving of emblems associated with one of Henry VIII's wives - the appearance of Anne Boleyn's initials implies a date before her execution in 1536.[14] It may simply have been the presence of crosses which made the pattern seem suitable for the decoration of chapels, although the crosses are hardly intelligible as such on the coves of the screen and stalls of King's College Chapel, which do not provide sufficient room for a single full repeat of the motif. Whether its early Christian origins might have influenced its choice for decorating the entire ceiling at St James's Palace can only be a matter for speculation, in the absence of any firm evidence. While it is possible that the design was chosen to carry the heraldic badges of Henry and his Protestant queen in an early manifestation of Protestant identification with the early Church it is perhaps more likely that it was selected simply in accordance with current fashionable tastes for Renaissance decorative motifs.

Fig. 20. Serlio, Book IV, f. 68v, bottom left (Dover facsimile of The Five Books of Architecture, 1611).

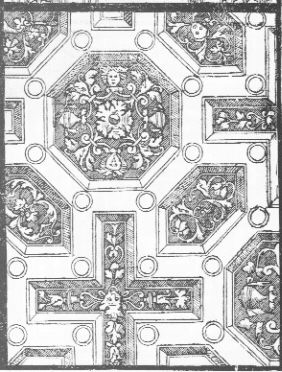

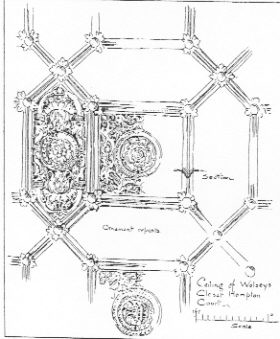

The second Henrician ceiling of c.1540 which uses a pattern to be found in Serlio was created in the room at Hampton Court christened in the nineteenth century 'Wolsey's Closet' (Figs. 21 & 22).

Fig. 21. Top: Serlio, Book IV, f. 69r, top right (Dover facsimile of The Five Books of Architecture, 1611); bottom: drawing of detail of ‘Wolsey’s Closet’ ceiling (from M Jourdain, English Decorative Plasterwork of the Renaissance, 1926).

The decoration of the room is partly the result of nineteenth-century remodelling and the ceiling must certainly have post-dated the cardinal, since it includes the Prince of Wales' feathers, alluding to the birth of Prince Edward in 1537.[15] However, although this particular use of the 'Serlian' pattern post-dates the publication of his book (and follows the style of decoration described and illustrated by Serlio very closely, with patterned fields and plain ribs), it was not the first occasion on which this rib design had been used on an English ceiling. An apparently much earlier example was to be found in one of the offices of New Palace Yard, Westminster, and was drawn by two nineteenth-century artists before its demolition, showing the 'Serlian' rib design combined with Gothic cusped ornament around the edges of the fields, which Serlio either left plain or filled with 'antick'.[16] This would suggest that this was another pattern available to the Royal Works before it appeared in Serlio's published volume. Clearly patterns such as those popularised by Serlio’s book were available to avant-garde patrons prior to publication. The point has been made that there seems to be a ‘tendency for a burst of engraved ornament to appear after, rather than during, the birth of a style in a court centre’ and this would seem to apply to Serlio’s publication of designs that had already been used in Italian and English court settings.[17] It is possible that loose sheets from the book circulated before being bound and published;[18] or perhaps drawings were transmitted by way of the Italian artists working for Cardinal Wolsey and Henry, or the diplomats who travelled on behalf of the cardinal and the king to Italy and France.

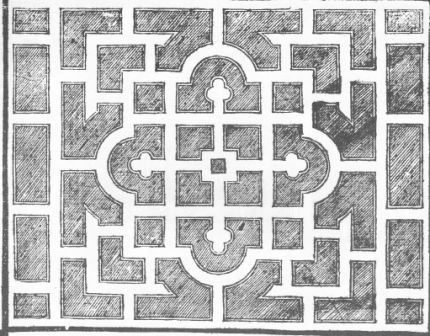

Whatever the means of transmission of these designs, two points need to be made in connection with their appearance in England. The first concerns Serlio's own sources, and his claim that the designs which he illustrated in Book IV, Chapter 12, were 'for the most part, taken from antiquity'.[19] This claim has tended to obscure the fact that several of the patterns would have been familiar to a medieval audience. For example, among the garden designs the barbed quatrefoil makes an appearance (Fig. 22), a motif found in decorative work in many different media throughout the Gothic period; and the hexagonal-armed cross which occurs in several of the ceiling patterns can also be found in Gothic vaulting (see Fig. 20).

Fig. 22. Serlio, Book IV, f. 69v, top left (Dover facsimile of The Five Books of Architecture, 1611).

This is not to deny the subsequent importance of Serlio (especially his Books III and IV) as a transmitter and populariser of many aspects of contemporary Italian design, but rather to suggest that, in the sphere of ornament, he drew together designs from a living European heritage which did not derive exclusively from Roman antiquity nor the Italian Renaissance and which did not, necessarily, need to rely on published sources for its transmission. Furthermore, the publication of designs which had originated in court circles probably meant that they were thus devalued in the eyes of their fashion-conscious patrons, providing the stimulus for further innovations from court artists.

The second point arising from the use of 'Serlian' designs in England relates to the way in which they were perceived by English craftsmen. The ceiling layout for Wolsey's lodging at Hampton Court (Fig. 13) can be associated most readily with Serlio's eight-pointed star design (Fig. 23), but the complex patterns created by the additional ribs in the English ceiling tend to blur the simple geometry of Serlio's outline and lend it a Gothic flavour. Moreover, it was in this form of a star with eight kite-shaped arms that the design became one of the most popular of rib-layouts during the remainder of the sixteenth century. Reference has also been made to the use of cusping to decorate apparently Renaissance rib patterns, and it would seem that English craftsmen found no difficulty in assimilating these imported designs and interpreting them within the context of their native decorative vocabulary.

Fig. 23. Serlio, Book IV, f. 68v, bottom right (Dover facsimile of The Five Books of Architecture, 1611).

What is more, as has already been pointed out, Wolsey's ceilings do not follow Serlio in the application of 'antick' ornament to the fields between the ribs (unlike the two Henrician ceilings of c.1540). It is the ribs themselves which carry the decoration and it was this innovatory feature which was to have the greatest impact on later plaster ceilings. It would be quite characteristic of English sixteenth-century art and architecture that an Italianate style of decoration and a novel method of production should be combined on Wolsey's ceilings with rib designs which echo the English Gothic tradition.

White or coloured ceilings in the Royal Works?

It is difficult to be certain how far, in a royal context, the whiteness of plaster was a factor in its acceptance as a material for making ceilings in the early sixteenth century. Although a plastered ceiling must have brought about a considerable improvement in the lighting level of small rooms like the Abbot's Parlour at Muchelney, this was not necessarily a characteristic which would have encouraged the use of plaster in royal palaces. There is no shortage of evidence to demonstrate the highly-coloured nature of the decorative schemes which were devised for the state rooms in Henry VIII's palaces, once the plasterers and joiners had completed their tasks. Even when ceilings were whitewashed this was usually only a preliminary measure before decorative paintwork was applied. Moreover, if a white ceiling was required there was no reason why white paint or whitewash could not have been used on a timber roof. It seems likely, therefore, that it was the speed with which plaster could be applied, and its cheapness and availability relative to timber, which encouraged its use in the Royal Works.

There was, however, one aspect of royal ceiling decoration which may have been a factor in the emergence of plaster as a decorative, rather than merely utilitarian, material. In the 1530s there are several references to the decoration of fret ceilings where the battens were painted white, and where the white paint would still be visible after the application of additional ornament. This is recorded first at Greenwich in 1533, where Andrew Wright and John Hethe painted white hundreds of yards of 'Batens off the Frett' in the king's privy chamber, the queen's bedchamber and the queen's presence chamber.[20] Two years later, the same treatment was recorded at Hampton Court where, in January and February, the painters were 'whityng of the battenys in the Rouffys of the quenys newe lodgyng and the herbers at the mownte';[21] and repeating the process, in November and December, in the king's privy closet.[22]

Once the ribs of fret ceilings had been painted white it must have become obvious that plaster could successfully perform the same role as timber in the creation of the frets themselves. It may be that an entry for Greenwich from September 1533 records such a realisation, since the plasterers were 'Workyng upon the new plasterynge withe whyte plaster the Frettes over the councell Chamber'.[23] This may only represent repair work, but it sounds as though rather more was involved than the usual washing with white plaster which occupied the plasterers' time elsewhere. If so, this entry chronicles a development in the Royal Works of some significance for decorative plasterwork.

Courtly ceilings in the 1530s and 1540s

A surviving parallel to this documentary evidence, also from the 1530s, lends weight to the suggestion that this was a decade in which the potential of plaster as a decorative medium began to be explored in courtly circles. Between 1530 and 1539 Robert King was Abbot of Thame, where he redecorated the abbot's lodgings and added a three-storey tower for his own use at one end of the entrance range.[24] In a room on the first floor (now known as the library) there is a boarded ceiling, with three cross-beams exposed, between which narrow wooden ribs are laid in a diamond pattern, with small escutcheons placed over the intersections; the frieze beneath carries Robert King's name. In contrast to this library ceiling, the abbot used plaster as well as timber in the creation of an exquisitely decorated room, occupying the whole of the first floor of his new tower, now known as the Abbot's Parlour (Fig. 24).

Fig. 24. Ceiling and frieze in the Abbot’s Parlour, Thame, Oxon.

The importance of the room for this study lies not in the beautiful Renaissance 'antick' decoration applied to the frieze and soffits of the cross-beams (with a large hexagonal pendant at the central intersection), but in the plastered fields created by the cross-beams which divide the ceiling into four. In one of these quarters there survive ceiling ribs in plaster, reminiscent of those at Great Chalfield Manor (Fig. 9). They must originally have extended over the whole ceiling, creating a pattern of small squares to relieve the plain white surfaces without distracting attention from the ornate carving which is the highlight of the room.

Just such a simple design, executed with less than perfect dexterity, is exactly what one would expect of an experiment in a new medium. The 'naive' quality of the plasterwork is in marked contrast to the extreme sophistication of the wood-carving, which demonstrates that Abbot King was in a position to patronise the best craftsmen he could command. It is unlikely that he would have been satisfied with less than the highest level of plastering skill then available; but at this stage the plasterers were still a long way behind the carvers and joiners.

Almost identical wood-carving is to be found at Nether Winchendon House, Buckinghamshire, refurbished by Sir John Daunce between 1527 and 1545; and friezes from Notley Abbey (now at Weston Manor, Oxfordshire), created for Abbot Richard Ridge between 1529-39, appear to be by the same hand. It has been suggested that since Sir John Daunce was a successful courtier and one of Henry VIII's privy councillors for many years, he may have had access not only to the latest fashions in interior decoration at court but also to the craftsmen who created them.[25] It is also possible that it was through the channel of the ecclesiastical patrons and their familiarity with the patronage of Cardinal Wolsey that such fashionable and refined wood-carving reached this part of the country in the 1530s.

In either event, one is led to wonder whether the plasterer of the Abbot's Parlour at Thame Park was also court-based. It seems that the ability to produce a smooth plaster surface was not a skill to be found throughout the country, as Cardinal Wolsey's agent, Robert Brown, found in 1530. Brown was in charge of the refurbishment of the Archbishop's Palace at Southwell, Nottinghamshire (to which Wolsey was to retire), but was finding it difficult to obtain craftsmen with the expertise required for 'castyng of your galery with lyme and heyre, according as mr. Holgik, your surveyor lately wrote to me, of truthe here be no workmene in this cuntrie to my knowledge that cane werke after any suche maner. Wherof yf your grace will have it so wrought, pleise hit you to command your surveyor to send doune in to the cuntrie some of your awne workmen.'[26] From the limited records available it is clear that Wolsey made use of the talents of native London plasterers, and it seems likely that Abbot King, too, would have had to bring a plasterer from the capital. If that craftsman had worked at sites where he could have seen fret ceilings using timber ribs, this might have inspired him to attempt the same kind of decorative effect in plaster; or perhaps it was at the suggestion of the patron himself. This may seem too speculative a train of thought, but it is put forward to underline the fact that, as at Acton Court, experimentation, albeit of an extremely rudimentary kind, was already taking place in English plasterwork in the 1530s, before Nicholas Bellin reached these shores.

It is not surprising that very few examples of such unsophisticated plasterwork have survived, but two ceilings point to continuing experiment of this kind in houses belonging to courtiers in Henry VIII's circle. On the estate of Sir Thomas Poynings at Westenhanger, Kent, stood a substantial dwelling, possibly the bailiff's house, in which 'a fine plaster coved ceiling' survived

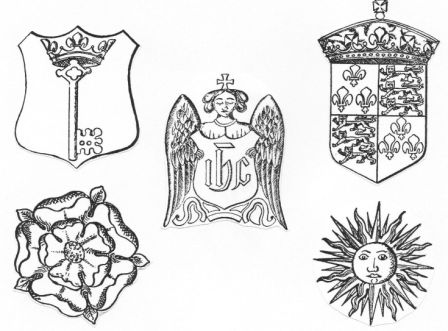

until the early years of the twentieth century.[27] This ceiling was decorated with heraldic badges and devices which included the Poynings' badge of a crown above a key (Fig. 25). As Westenhanger was surrendered by Sir Thomas to Henry VIII in 1540 the ceiling must have been in place before that date. Unfortunately, there is no indication of how the badges were incorporated in the ceiling.

Fig. 25. Heraldic badges from a lost ceiling at Westenhanger Manor, Kent.

The second example is even more securely datable by its heraldry. West Horsley Place, Surrey, was granted by Edward VI to Sir Anthony Browne, Master of the Horse to Henry VIII and guardian of his two younger children, early in 1547. Sir Anthony himself died in 1548 and so had only a year in which to make his mark on his newly-acquired mansion. Nevertheless, the great chamber on the first floor still bears witness to his occupation in the form of the remains of the coved plaster ceiling inserted by him (Fig. 26). The surface of the cove is divided by narrow plaster ribs laid out in a slightly simplified version of the Wolsey ceiling at Hampton Court (Fig.13). The ribs are simple strips with an extremely plain profile and an attempt at 'moulding' painted along their sides. In many of the panels thus created the badges and initials of Sir Anthony and his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of the ninth Earl of Kildare, were displayed.[28] This ceiling provides the best documented evidence of the transmigration of court style from the palaces of Henry VIII to the houses of his courtiers. The change in the choice of material in which to embody that style was of the utmost significance for the future development of decorative plasterwork.

It is perhaps significant that West Horsley Place was not Sir Anthony Browne's chief residence, which was Battle Abbey. The latter had been given to him by Henry VIII in 1538 and he had already converted some of the monastic buildings to create a domestic dwelling of considerable splendour.[29] Nothing survives of the interior decoration of Battle Abbey from that date, but it is conceivable that Browne would have felt more at liberty to experiment with something as novel as a plaster ceiling in one of his lesser houses than he would have in his main seat.

A similarly experimental character can be observed in a plasterwork ceiling in the main house of a courtier of somewhat lesser status than Sir Anthony Browne. Holcombe Court, Devon, was built by Sir Roger Bluet c.1520-30. Bluet lived until 1566 and it his heraldic badges that decorate the long gallery ceiling. The rather ungainly layout of the ceiling rib-design suggests it was probably installed somewhat earlier than that date (Fig. 27).[30] Bluet came from an established Devon gentry family and was 'a friend of the Lord Protector Somerset', which might account for his interest in the emergent mode of ceiling decoration.[31] Unlike the plasterer at West Horsley Place, the craftsman in Devon ran the narrow ribs by hand using a thumb mould, which produced the type of profile which was to become the norm in ceilings of this kind.

These early plaster ceilings show little evidence in their design and execution of foreign influence, and it seems reasonable to assume that they were the work of native plasterers, working with lime plaster, interpreting court fashions in ceiling design within the context of the native decorative vocabulary with which they were familiar. From the point-of-view of patrons, experimentation with plaster as a decorative medium seems to have taken place in gentry houses or in the secondary houses of courtiers and aristocrats rather than in the royal palaces. That was to change when Henry VIII made the decision to build Nonsuch Palace.

Fig. 26. Detail of the ceiling of the gallery at West Horsley Place, Surrey.

Fig. 27. The ceiling of the gallery at Holcombe Court, Devon.

Fig. 27. The ceiling of the gallery at Holcombe Court, Devon.

Nonsuch Palace, Surrey 1538-45

Against this background of experiment and innovation in the sphere of interior decoration, both in the royal palaces and in the houses of courtiers, was conceived an extraordinary scheme to decorate a large part of the exterior of Henry VIII's new palace in Surrey with panels of decorative plasterwork in high relief. Nonsuch Palace was intended to be a 'nonpareil' and in this respect, at least, there was no precedent for external work on such a vast scale, even in Italy; building work began in 1538 and continued on the exterior until at least 1545.

One would not expect to find another building decorated in the same way as Nonsuch, since that would have undermined Henry's ambition to create a building without parallel; and it would have been a rash courtier who risked arousing his monarch's wrath by appearing to vie with him on such a princely scale. The enduring fame of Nonsuch, however, lasted up to the time of its demolition in the late-seventeenth century and rested almost entirely on the magnificence of its exterior decoration, which elicited expressions of amazement from a succession of admiring visitors. That there was, indeed, nothing else quite like it probably accounts for the false assumption made by one Dutch visitor that the walls were 'decorated with ashlar and skilfully carved sculpture of very pure white stones'.[32]

Partly because of the coincidence of his arrival in England in 1537, and partly because of his experience at Fontainebleau, it is usually assumed that Nicholas Bellin of Modena was the artist/artificer with overall responsibility for the external decoration of Nonsuch Palace.[33] This would have included the panels of plasterwork, as well as the carved and gilded slate borders around them for which he received payment. Bellin is the most likely candidate for such a role, but it should be borne in mind that the decorative consoles and other work in plaster at Acton Court of 1535 preceded his arrival in England and there may have been other artists working for Henry VIII who would have been capable of masterminding the work at Nonsuch, whose names do not figure in the surviving documents.

The accounts relating to the building of Nonsuch (1538-45) are woefully incomplete, but Bellin is the only one of the numerous Italian artists employed by Henry VIII who can indubitably be associated with the palace. It is Bellin's career in England that has given rise to the widespread notion that there were numerous other Italian plasterers working for Henry VIII, despite the absence of any evidence that the other Italian artists employed by the king were engaged on this kind of work. If Bellin brought assistants with him from France they are more likely to have been French or Dutch, like the men recorded as working with him on Henry VIII's tomb in 1544 and living with him as his servants.[34]

There is, however, some evidence to identify other craftsmen involved in the creation of the plasterwork at Nonsuch but the precise nature of their roles is as elusive as that of Bellin himself. In 1541 a payment of £6 was made to 'Moden [ie Nicholas Bellin of Modena] & his Company working uppon slate' while £20 was paid to 'kendall & his company occupiede in makinge of molds for the walls xxiiij'.[35]

Bellin's company certainly included Frenchmen, since some of the slate fragments excavated carried instructions in French for positioning them on the structural timbers.[36] Kendall was presumably an Englishman with some involvement in the creation of the exterior wall decoration but the term 'molds' carried so many different meanings in the sixteenth century that it is difficult to interpret more precisely in this context. If Professor Biddle is correct in identifying him with William Kendall of London, a carver who worked for the king, it would be tempting to envisage his work as the carving of reverse wooden moulds for the plasterwork; but most of the panels appear to have been modelled around armatures rather than fashioned in moulds. The rate of pay for Kendall and his men over the five-week period in 1541 averages out at less than 39d per man per week, which does not suggest that they were classified as highly-skilled men, although if they were not working full-time the rate would naturally be higher.

Kendall himself does not appear to have been in receipt of an annuity such as was paid to Bellin and to another foreigner, Giles Gering, described by the king in 1545 in connection with Nonsuch as 'overseer of certain of our white workes'.[37] Dent suggested that since Gering was designated 'the moldemaker at Nonsuch' in 1545, he had replaced Kendall in this role; but it seems more likely that he had replaced Bellin, since his annuity of £20 was paid at the same rate as that of the Italian.[38] This scanty evidence does at least suggest that, although overall control was probably in the hands of foreigners, the teams responsible for the execution of the Nonsuch plasterwork comprised more than a handful of men and that some of them were English. The experience of working on Nonsuch must have made an impact on the craftsmen concerned and opened the eyes of some native artisans to the decorative potential of lime plaster.

The men carrying out the routine plastering of the palace must also have seen, and wondered at, the creation of the exterior decoration in plaster. They were drawn from the ranks of plasterers (mostly Londoners) who performed the same tasks in other royal palaces. The names of only five plasterers appear in the detailed accounts which survive for the five pay periods between 22 April and 14 September 1538. In June-July 1538 riding costs were paid to 'Richard Hayward, plaister, for his costs & expences Rydyng abowe to take the said here by the space of ij daies', but at this stage of the building's construction plasterers can hardly have been needed.[39] During the five pay periods a single plasterer was listed only twice, compared with twenty-four masons, twenty-seven bricklayers and forty-one carpenters in May-June. During eight weeks in May, June and July the plasterer, Richard Procter, worked a total of only twenty-one days, accompanied by three 'servitors' - John Kelly, Morris Watkins and Davy Welshe.[40] All four were employed elsewhere in the Royal Works, and although Watkins and Welshe are recorded only at Oatlands (1537-38), Kelly worked at Westminster, Oatlands and Hampton Court (1530-38) and Procter at Hampton Court, Oatlands, Greenwich, Chobham and Dartford (1535-42). It is obvious from the quantities of hair and plaster of Paris which were stockpiled that the number of plasterers must have swelled considerably in the ensuing years; precise numbers are not available, but Robert Lorde's summary accounts record a total of £125 paid to unnamed plasterers between 1538 and 1545.[41] Equally anonymous are the four plasterers, with five assistants, who were engaged on routine work at Whitehall alongside Bellin and his mortar-makers at some point between 1537-41, but they are even more likely to have been drawn from the ranks of London plasterers.[42]

There was, indeed, no likelihood of any of these English plasterers matching the Italian in artistry and there is no evidence that the first-hand observation of the decorative potential of plaster had any immediate influence on English plasterwork; nor is there is any evidence of either Bellin or Gering transmitting their skills directly to native artisans. Although Nicholas Bellin remained in England until his death in 1569, there is no record to suggest that decorative plasterwork was a continuing element in his own employment as a royal decorator. The only examples of internal plasterwork for which he is known to have been responsible were chimneypieces, but none of his royal commissions appears to have survived, although Professor Biddle has argued convincingly that the overmantel in the Star Chamber of Broughton Castle (Fig. 28) shows every sign of belonging to a 'school of Nonsuch', and was probably executed by someone who had worked at the palace.[43]

Fig. 28. Plaster overmantel now in the King’s Chamber, Broughton Castle, Oxon.

Bellin, himself, may have been the artist responsible for this sophisticated chimneypiece but Giles Gering is an alternative candidate, since it seems likely that he was pursuing commissions which may have involved plasterwork outside the Royal Works. When he was criticised by Henry VIII for his inadequate supervision of the work at Nonsuch in 1545, Gering claimed in his defence that members of the king's Council knew 'well ynough the cause of his absence and were contented that he shulde be allowed his wage here all the saide tyme of his being awaie.'[44] This suggests that Gering was neglecting his royal duties in favour of work in houses belonging to members of the court but does not indicate the nature of the work he was undertaking. Equally uninformative is the bare fact of his employment by the Duke of Somerset in April-September 1548, together with the mason/sculptor, William Cure I, who had also been employed at Nonsuch.[45] Gering's royal pension continued to be paid until 1548 but no further evidence is available to construct his career after that date and his hypothetical role as a transmitter of the influence of Nonsuch to the houses of a high-ranking courtier like Somerset cannot be substantiated.

Absence of artistic training for English plasterers

The influence of foreign artists like Bellin and Gering was always going to be limited stylistically by the disparity between their training and that of their English counterparts. As was the case with so many Renaissance artists, Bellin's versatility allowed him to design buildings, to paint, carve and model - anything from monumental tombs to costumes for the Revels - all of which he undertook while in England. This was in marked contrast to the restrictive practices of the English guilds, forever attempting to draw demarcation lines around the work of the craftsmen they represented.

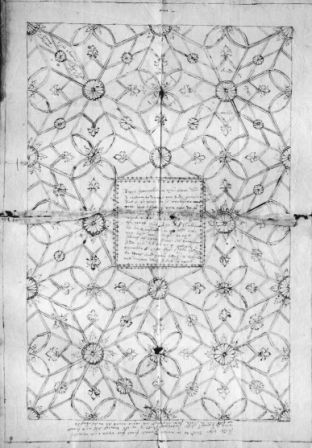

Underlying such versatility lay a thorough grounding in the art of drawing, especially figurative drawing, but such basic artistic skills were completely lacking in the training of English artisans, and one would not expect to find figurative plasterwork of the quality of Nonsuch executed by English craftsmen during the period under review. That this short-coming was keenly felt by at least one English plasterer is apparent in a drawing for a plaster ceiling at Ramsbury Hall, Wiltshire, which can be dated to c.1580-1601 (Fig. 29).[46] This appears to be a unique survival of a presentation drawing prepared by a plasterer for his patron, in this case, Mary Sidney, wife of the 2nd Earl of Pembroke. The fret design is clearly drawn and labelled with measurements for the depth of the pendants, but in the central square panel the plasterer has written, 'in this place did I mean to drawe my lordes armes But this plase is so troblesome vnto me that I Can not do it vnto my mynd But y will work your honer this Pece of Work that the lyk shall not be in England or else let me lose my lyfe in the seling of your havle at Ramsbury...' Ramsbury Hall was demolished in the late-seventeenth century and no records of its interior survive to show whether the plasterer was required to put his skills to the test.

Fig. 29. Plasterer’s design for the ceiling of the hall at Ramsbury Hall, Wilts. © Marquess of Bath.

It was presumably in the form of drawings like this that plasterers offered a choice of designs to their patrons. Even this level of skill in drawing was beyond some plasterers. The records of the remodelling of Old Thorndon Hall, Essex in the last quarter of the sixteenth century contain an entry for 1577 for a payment ‘To Grenewood the paynter by Richard Barfeld Playsterer for drawinge my master and ladyes armes with ynke, for the saide playsterer to grave armes by for the great chamber roufe’.[47] Henry Peacham was still bemoaning this woeful state of affairs in his Art of Drawing in 1606 ‘when scarce England can afoord vs a perfect penman or good cutter’.[48]

Apart from the Broughton Castle example, one looks in vain for chimneypieces in this 'Nonsuch style' in plaster in those courtier houses which were built or decorated in the mid-sixteenth century, either in London or elsewhere in the country. It is, of course, possible that they did exist but have not survived to the present day and were not recorded before they were demolished. The classicism of the sculptural style would have appealed to those exponents of classicism in architecture who were busy building during this period, especially to those men who were associated with Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset - Thomas Seymour, Sir John Thynne, Sir William Sharington, Sir Thomas Smith and William Cecil - and the Duke of Northumberland.[49] Almost nothing of the interior decoration of their houses has survived to lend weight to such a supposition, but where chimneypieces are still in situ, as at Lacock Abbey, they are of stone, not plaster. Sir William Sharington employed the mason, John Chapman, to carve a stone chimneypiece for him, and Chapman was subsequently employed by the Duke of Northumberland at Dudley Castle and by Sir John Thynne at Longleat.[50] In addition to Chapman, Thynne chose to employ the Frenchman, Allen Maynard, to carve chimneypieces in stone.[51]

On the available evidence it seems likely, therefore, that Bellin and Gering did not train sufficient plasterers to work in their 'Nonsuch style' once the palace was completed. Indeed, there would have been little incentive to establish a school to perpetuate their skills when Henry VIII wanted his palace to be like no other. In this situation a well-carved stone chimneypiece would clearly be the preferable alternative to modelled plaster; and this is what the scant surviving evidence suggests would have been found in the courtier houses of the mid-century.

At the most general level, the achievement of Nonsuch must have served to raise the status of plaster as a decorative medium in the minds of courtly patrons. It would have made them more responsive to the experiments already taking place with plaster and facilitated the flowering of decorative plasterwork which began in the latter half of the sixteenth century. The evidence for such courtly patronage of plasterers capable of decorative plasterwork will now be considered.

Royal ceilings after Henry VIII

After the death of Henry VIII there is no indication in the written records, and certainly no interior decoration surviving, to suggest that decorative plasterwork played any further part in royal interiors until 1582-84. The appointment of the first royal Master Plasterer in 1555 is, therefore, more likely to have reflected the increasing importance of smooth plaster as a surface covering, than to indicate experimentation with plaster as a decorative medium in the royal palaces.

Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth inherited a vast collection of palaces and smaller royal houses, many of which had been lavishly decorated by their father in trend-setting fashion. Maintenance was all that was required and, according to the Royal Works' accounts, was all that most royal dwellings received, especially under the stringently economical regime imposed by Elizabeth.

There is, moreover, one mention of a ceiling decorated for her in 1553 which suggests that the Henrician manner was still regarded as the most appropriate for his successor. Somerset House had been left empty at the fall of the Duke of Somerset in 1551, and it is quite likely that the interior decoration had not been completed by that date, since considerable sums were expended in 1553 to render it an appropriate London home for Princess Elizabeth. The Sergeant Painter was paid £132 for painting and trimming the roof of the withdrawing chamber and other work, which would hardly have been necessary if the room had recently been finished by the duke.[52] Further light is thrown on the nature of this ceiling decoration by entries in the Works' accounts from the late 1560s. Elizabeth had some rebuilding and redecoration carried out which involved painters in repairing and mending 'the roofe of the withdrawing chamber with fyne burnished golde and collours and a garnishe of leade all gilte.'[53] This sounds remarkably similar to those ceilings of Henry VIII's reign which were decorated with wooden ribs filled with cast lead enrichment, before being painted and gilded, and not at all like a decorative plaster ceiling.

Aristocratic and courtier patronage of decorative plasterwork, 1547-84

If the monarchy was slow to exploit the decorative potential of plasterwork in interior decoration, then one must return to the trail leading from Westenhanger and West Horsley Place and search for indications of the continuing deployment of decorative plasterwork in the houses of those aristocrats and courtiers whose patronage was likely to inspire their social inferiors to emulation. The brief chronological survey of such houses between the death of Henry VIII and c.1584 which follows, will provide evidence in support of this hypothesis. Although the sample is rather small, most of the examples included can be dated fairly accurately, which is not the case with much of the sixteenth-century plasterwork surviving in the houses of lesser courtiers, gentry or merchants. During the reign of Edward VI the aristocrats who wielded power until the succession of Queen Mary, in 1553, demonstrated the importance attached to architecture as a visible expression of their authority by their building projects – either in or near London and or in those parts of the country where their regional power was concentrated.[54] Nothing survives of the Duke of Somerset's interior decoration at his London palace, Somerset House, nor at his semi-suburban mansion, Syon House, Middlesex, nor at his West Country houses of Wolf Hall and Bedwyn Brail, Wiltshire, and Berry Pomeroy, Devon. There is a hint, but no more than that, that decorative plasterwork might have been involved at one or more of these houses in the bald reference to the employment by Somerset of Giles Gering (the senior plasterer who supervised the completion of the work at Nonsuch) between April and September 1548.[55] On the other hand, it is quite possible that the interiors of Somerset House, at least, had not been completed by the time of the duke's downfall in 1551, as suggested above. Equally ephemeral was the major building project of Somerset's rival and successor, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, at Dudley Castle, Staffordshire.

Those courtiers who were close to the centre of power followed the example of their leaders in attempting to give expression to their position through their buildings but, again, nothing is left to show whether decorative plasterwork was deployed by Sir John Thynne (at Brentford, Middlesex, or the first phase of Longleat, Wiltshire), Sir William Sharington (at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire), or Thomas Seymour (at Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire). It is striking that so many of these

projects were located in, or near, London and in the counties of west and south-west England, and it is possible that the appearance of decorative plasterwork in these areas earlier than in the rest of the country was connected with the building activities of these courtiers.

Longleat, Wiltshire

It is not until 1555, however, that the next certain evidence appears that decorative plasterwork was continuing to be the subject of experiment in the houses of aristocrats and leading courtiers. In March of that year a letter was sent from Sir William Cavendish to Sir John Thynne, who was by then engaged on the interior decoration of Longleat, expressing the former's eagerness to obtain the services of the 'connyng plaisterer At longlete which hath in your hall and in other places of your house made dyverse pendaunts and other pretye thynges' and asking for him to be sent to Derbyshire to work on the hall at Chatsworth, when he had concluded his work for Thynne.[56] The significance of Sir William Cavendish's letter lies in the reference to pendants, which clearly indicates that the plasterer was decorating the ceilings of the house rather than the chimneypieces, and suggests that he was working in the largely Gothic-inspired style of the majority of Henrician palace ceilings, rather than in the Franco-Italian Renaissance mode of Nicholas Bellin. Previous accounts of early plasterwork have identified this plasterer with Charles Williams, who wrote to Sir John Thynne in 1547 seeking employment. Although Williams had travelled in Italy and claimed to have become expert in several areas of artistic endeavour, decorative plasterwork was not one of them; and there is absolutely no reason to number him among the ranks of early English plasterers.

From Cavendish's letter it may be concluded that he intended at least some of Chatsworth's interiors to be ornamented with plasterwork; but it would appear that this was slow to materialise since Bess of Hardwick (by this time widowed and remarried to Sir William St Loe) wrote again to Thynne in 1560. This letter is, however, rather less informative about the type of work to be undertaken, merely asking Thynne 'to spare me your /plaisterer ['mason' crossed through] that flowred [floored, not ‘flowered’] your halle.'[57] Bess may not even be requesting the services of the same plasterer as her late husband, since routine work only is referred to, but the evidence is hardly conclusive.

Copt Hall, Essex

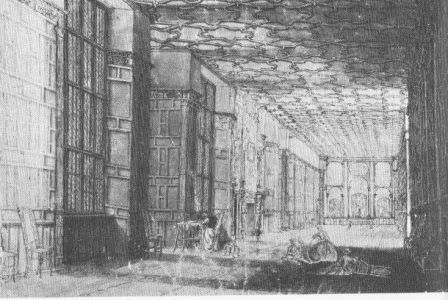

From 1564 Sir Thomas Heneage, one of Elizabeth's favourite courtiers, refashioned Copthall, Essex, to produce a mansion splendid enough to entertain the queen on several occasions.[58] One of the most striking features of the mansion which emerged was the long gallery, extending along the whole length of the east range. The interior of this room was recorded in a drawing by Sir Roger Newdigate before the house was demolished in the eighteenth century. This appears to depict a plaster ceiling decorated with a simple narrow-rib pattern of barbed quatrefoils connected by intersecting diagonals (Fig. 30); at the intersections additional interest is supplied by large, projecting bosses (or small pendants - the detail of the drawing is not clear enough to allow certainty on the point). The simplicity of the design would accord with a date in Sir Thomas's lifetime (he died in 1595), and probably earlier in Elizabeth's reign rather than later. Allowing some time for the creation of the long gallery itself, the ceiling may well have been decorated by the late 1560s.

Fig. 30. Sir Roger Newdigate’s drawing of the long gallery at Copt Hall, Essex, before its demolition.

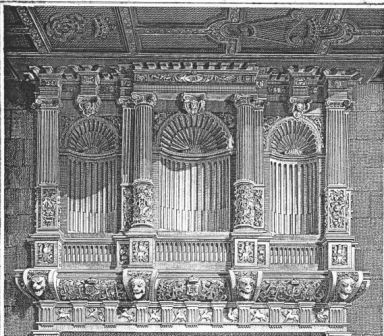

Charterhouse, London

Almost contemporary with Heneage’s building work at Copthall was the refurbishment of the Charterhouse (just to the north of the old City walls) undertaken by Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk. The conversion of the monastic buildings into a domestic dwelling had been started by Lord North, but some of the interior decoration can be dated to the duke's occupancy between 1565 and 1571. To this period belongs the redecoration of the great chamber which was conceived in a dynastically assertive manner. The simple curvilinear rib design of the plaster ceiling creates fields which are decorated solely with repetitious arms, badges and mottoes of the Howard family. The Charterhouse was badly affected by bomb damage in 1939-45, including this ceiling, and the post-war restoration in fibrous plaster, based on photographs and surviving fragments, may not be entirely accurate. One alcove survived the destruction and its hand-run ribs provide a flavour of the original appearance of the ceiling overall (Fig. 31). A reference in 1612 to the room as the ‘gilded chamber’ suggests that the ribs may always have been gilded.[59]

Fig. 31. Ceiling of the alcove in the great chamber of the Charterhouse (c.1570).

New Hall, Essex

The use of such heraldry for ornamental purposes can be extremely helpful in identifying the patron of decorative plasterwork and in dating it, and it is the arms of Thomas Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Sussex, which indicate that he was responsible for the sixteenth-century plasterwork at New Hall, Essex, which he acquired in 1573. The existing north range was remodelled by him shortly afterwards and is the only part of the house still standing. According to an eighteenth-century plan of the house, the south facade had seven symmetrical canted bay windows rising through the two storeys of the range.[60] On the first floor, these bays still retained their plaster ribbed and vaulted ceilings in 1921, and the RCHME Inspector included a sketch of the rib design in his report, noting that three of them incorporated the arms of the earl within a Garter.[61]

Sheffield Manor Lodge, Yorkshire

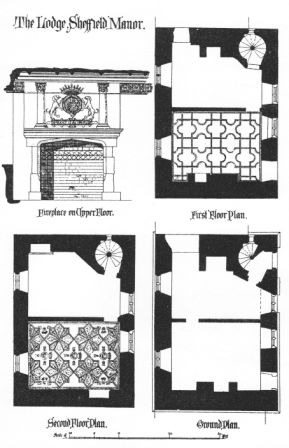

Further examples of aristocratic patronage of decorative plasterwork survive from the mid-1570s, suggesting the increasing availability of plasterers with the skills to execute decorative work in the style and to the standard of these exacting patrons. Bess of Hardwick's fourth husband, George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, undertook a major rebuilding programme at Sheffield Manor, Yorkshire, from 1574, in order to provide additional accommodation to that available at his main residence, Sheffield Castle, for his unwilling house guest, Mary, Queen of Scots. The enlarged manor house itself gradually became ruinous after 1706, but there is one survival from the earl's refurbishment in the shape of the Turret House, a gatehouse and lodge, which contains a banqueting room on the second floor, elaborately decorated with a plaster ceiling and overmantel (Figs. 32).[62]

Fig. 32. Plans of the ceilings and elevation of the chimneypiece at Sheffield Manor Lodge, Yorkshire (Journal of British Archaeological Association, Vol XXX (1874), 42).

The narrow-rib ceiling is laid out according to the 'cross and star' pattern, familiar from Hampton Court, but without bosses or pendants. Grotesque bearded masks are placed in three of the arms of the central crosses while the fourth contains an earl's coronet, with the Talbot badge (a talbot dog), encircled by a Garter, at the centre; female masks are deployed in the half-crosses along the sides of the ceiling. In the kite-shaped fields of the stars, four different floral patterns are arranged to fill the available space. Two rows of alternating 'S' scrolls make up the frieze, with bell-shaped flowers between them. David Bostwick points out that the frieze design is the same as that used in the border of the Tobias table carpet at Hardwick New Hall, dated 1579.[63] This provides a clear example of the use of the same source by craftsmen working in very different media. In this case one is tempted to wonder whether it was the patron who provided the pattern on both occasions, or whether it was handed from one craftsman to another, working for the same patron. Perhaps the former hypothesis is given added weight by the appearance of the same design in title-page borders used by the publisher J Cawood in the 1550s and 60s. Books such as Bishop Bonner’s A profitable and necessarye doctrine, with certayne homelies (1555), or even Petrarch’s The tryumphes (?1555), might well have been found in the collection of a patron like Shrewsbury.[64]

An architectural surround is attempted in the overmantel (Fig. 53), with its stubby Corinthian columns flanking further evidence of the status of the owner of the building, in the shape of the Talbot coat-of-arms within a Garter, resting on the Talbot motto, supported by two talbots and surmounted by an outsize earl's coronet. This ostentatious display was preceded on the floor below by a very simple ceiling of narrow-rib design, with no additional embellishment.

Ormond Castle, Ireland

In Ireland a major example of aristocratic patronage of plasterwork in this decade is to be found at Ormond Castle, County Tipperary.[65] Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormond, cousin and favourite of Elizabeth, transformed what had been a medieval castle into an up-to-date dwelling for a courtier by the addition of a new north range incorporating a suite of state rooms. Four of these rooms retain elaborate plaster decoration, including ceilings, friezes and overmantels.[66] Apart from the narrow ribs, which were presumably hand-run, the motifs throughout these rooms were produced from moulds. The Butler coat-of-arms and badges and Thomas Butler's own personal badge feature strongly on the friezes and overmantels in the ground-floor parlour (Figs. 33-4) and in the first-floor 'new dining chamber'. The strapwork cartouche carrying Thomas Ormond's initials and his badge is attached at the cardinal points to a circular band bearing his motto, 'COME IE TROVE', with the figures of the date, 1575, all reversed. Such heraldic displays are entirely consistent with what one would expect in plasterwork of this date and they have figured in all the ceilings so far.

Fig. 33. Section of the frieze in the parlour of Ormond Castle, Ireland (1575).

Fig. 34. Section of the overmantel in the parlour of Ormond Castle, Ireland (1575).

Ormond Castle is unusual in that it also provides examples of decoration where the motifs have been selected with more than dynastic display in mind. The long gallery is dedicated to expressions of loyalty to Elizabeth as monarch, with the fields of the ceiling design filled in the customary manner with the Tudor coat-of-arms, with Elizabeth's supporters; Tudor badges such as the portcullis and Tudor rose; and Elizabeth's crowned initials. The frieze, however, suggests that this reading of the ceiling is perhaps an over-simplification and that Thomas Butler wished the plasterwork of the room as a whole to convey a more reasoned political message, aimed specifically at the Irish spectators who would gather in his gallery. The frieze consists of roundels flanked by female figures standing within round-headed classical arches, separated by pilasters, all in medium-relief and all cast from moulds (Fig. 35). The roundels are of a design similar to those made for Cardinal Wolsey by Giovanni da Maiano at Hampton Court Palace; but instead of Roman emperors the garlands at Ormond Castle encircle three different designs, repeated around the long gallery - the Tudor coat-of-arms, beneath an imperial crown, alternates with portrait busts of Elizabeth and Edward VI, crowned and bearing sceptres, embodying the triumph of English Protestantism. The female figures in classical drapery are labelled 'IVSTICIA', clutching the hilt of her sword, the emblem of power as well as justice; and 'EQVETAS', carrying a pair of scales, indicating impartiality and fairness.

Fig. 35. Section of the long gallery frieze at Ormond Castle, with the bust of Queen Elizabeth flanked by the figures of Justice and Equity.

The political import of all this seems clear enough and would have been readily grasped at a period when many of the leading Irish rebels had, momentarily at least, submitted to Elizabeth, partly as a result of the earl's efforts.[67] Thomas Butler, loyal to the English Protestant monarchy, is advocating to the rebellious leaders of Roman Catholic Ireland the acceptance of the English 'imperium', which will bring the rule of law and the exercise of justice to their war-torn country.[68] Such an overtly political programme is unusual in the iconography of decorative plasterwork; what is not unusual is the co-existence of motifs of classical and Gothic inspiration to convey a single message.

The plasterwork of the long gallery is clearly intended as a political statement for public consumption. By contrast, in a large room off the long gallery, which is identified as the new great chamber or 'the Earl's Chamber', Thomas Butler introduced a more personal element into the plasterwork of the frieze. Alongside the Butler arms and strapwork cartouches of a purely decorative character (Fig. 47), appears a quotation, also framed within a strapwork cartouche, 'PLVES PENSE QVE E DERE'. This is a somewhat garbled version of the first line of a rondeau by the medieval French poet, Charles d'Orléans, bewailing the need 'to think more than is said' and to remain silent, concealing his inner torment.[69] In choosing such a motto from a courtly medieval poem Thomas Butler was perhaps showing himself in tune with the revival of romantic chivalry which was at the heart of the way Elizabeth organised her court and its social activities. Since the cause of the poet's torment is not identified, the first line of the poem remains enigmatic but it seems more likely that Thomas Butler was here indulging in the kind of courtly charade encouraged by his queen, rather than hinting at a genuinely broken heart.

Burghley House, Lincolnshire

There is documentary evidence to show that Elizabeth's most trusted courtier, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, decorated the long gallery of Burghley House, near Stamford, with plasterwork. In July 1578 Richard Shute wrote to his master that 'The Frett of the gallerye very neare the halfe thereof is also done',[70] and Thomas Cecil, his elder son, confirmed that the gallery would soon be finished despite the slow progress of the 'fretting which is a lingering and costly work.'[71] By the end of the seventeenth century major alterations to the interior of Burghley House had swept away the long gallery, together with all traces of its plasterwork. There is, however, one surviving piece of plasterwork at Burghley House which appears to date from Lord Burghley's time.[72] In the soffit of the projecting bay at the south-east corner of what is now the "Hell" Staircase can be seen the truncated ribs and bosses of a ceiling with its frieze (Figs. 36-7). Although the fragment is extremely small, enough detail remains to indicate the high quality of the work which William

Fig. 36. Ceiling fragment in bay of the “Hell” staircase at Burghley House, Lincs.

Fig. 37. Frieze and pendant on ceiling fragment at Burghley House.

Cecil was able to command. The simple narrow-rib design is enlivened by bosses of two designs, which are so large and elaborate that they almost qualify as pendants. Both are surrounded by eight frilly leaves which curl between the ribs. Although they are rather damaged, the leaves are so elaborate that one is tempted to wonder whether they were inspired by the acanthus leaves of

Corinthian capitals, such as those illustrated by Serlio in Book III, f 65r or Book IV, f 59r. The larger of the two has four small human faces around its lower tip (Fig. 38). This was, perhaps, a conceit which was felt to be appropriate to a window bay, since the pendant in the bay of the great chamber at Stockton House, Wiltshire, displays exactly the same feature.

Fig. 38. Pendant with four small faces on the ceiling fragment at Burghley House.

Fig. 38. Pendant with four small faces on the ceiling fragment at Burghley House.

The frieze at Burghley is quite shallow, decorated with repeating leafy scrolls and floral sprays.It has so far proved impossible to retrieve the exact sequence of construction for this area of the house, and it is therefore one can only speculate about the likely date of this plasterwork. The building of Burghley House fell into two distinct phases (Phase 1: 1550s-1563; Phase 2: 1575-1587) and at the end of the second phase, according to John Thorpe's plans of Burghley, the projecting bay adjoined the great staircase hall at the high end of the hall.[73] It might be assumed, therefore, that the decoration of the bay was part of this scheme, and could be dated in the late 1570s (like the long gallery plasterwork) or the 1580s. On the other hand, it seems possible that in the first phase of building work the great staircase was not located in its present position and the bay could have been part of a room into which the great staircase was subsequently inserted. Given the quality of the plasterwork and the documentary evidence for decorative plastering during the second phase, the balance of probability seems to be tilted slightly towards the later date.

Theobalds, Hertfordshire

The two building phases of Burghley House were separated by years in which Cecil's major expenditure on building projects was directed towards the completion of Theobalds in Hertfordshire.[74] Descriptions by contemporary visitors convey something of the magnificence of the interiors created by Cecil following the queen's first visit in 1571. Summerson concludes that, after that date Theobalds was no longer regarded solely as a nobleman's house but as an 'occasional palace' for the queen. In this light it is intriguing to read the description recorded by Rathgeb, secretary to the Duke of Wirtemberg, during their visit in 1592:

'Some rooms in particular have very beautiful and costly ceilings, which are skilfully wrought in joiner's work and elegantly coloured, as may be seen in the annexed sketch, the ground of which is prettily ornamented with blue colours, but the roses and other ornaments are gilded.'[75]

Fig. 39. Rathgeb’s sketch of a ceiling at Theobalds, Herts (1592).

Summerson suggests that this sketch (Fig. 39) could depict the ceiling of the long gallery, as it approximates the description of that room provided in the Parliamentary Survey of 1650; but it is clear that the decoration of several important rooms underwent alterations in 1603-04, during Robert Cecil's ownership of the house.[76] Whichever ceiling is shown in the drawing, it is the reference to joiner's work which is puzzling. The painting of the ceiling would effectively have disguised the material of which the ribs were made and one has to conclude either that Rathgeb was told that the ribs were of timber, or that his own experience led him to make that assumption.